Exhibition of the graphics and paintings by St. Petersburg artists Vladimir and Andrey Vetrogonskiy

“Vladimir Vetrogonskiy on the road. Andrey Vetrogonskiy at home” comprises two very different exhibitions forcibly integrated into one project. Vladimir Vetrogonskiy (1923—2002) is the father and Andrey Vetrogonskiy is the son, born in 1956.

Vladimir Vetrogonskiy on the road

In 1927, at his father’s will, a four-years old Vladimir Klimov got a new poetic surname, Vetrogonskiy. Its very sound, or, perhaps, internal dynamism of this surname, evokes the images of sea adventures and vast expanses. Life of Vladimir Vetrogonskiy, who moved to Literatotov Street in Saint Petersburg in the same year, was indeed full of wanderings. As a very young man, Vladimir Vetrogonskiy went through hell. In his diaries, the artist refers to the Leningrad Blockade as the freezing hell. His first trip to Europe took place right after the blockade was broken: the future artist was liberating Hamburg in the ranks of Red Army.

Much later Vladimir Vetrogonskiy became famous for his “On Volga Today” (1965) and “Volga-Baltic” (1972) graphic series that focused on the impressions gained on the road.

For 50 years of teaching and successful academic career Vladimir Vetrogonskiy had the chance to travel all around the world. He visited Poland, Italy, Bulgaria, Bangladesh, Belgium, Germany, Netherlands, Finland, Portugal, France, China, and Cuba.

It’s difficult to overestimate the significance of the experience a Soviet citizen could get when travelling to sister republics of Eastern Europe on a business or creative trip. Many saw a trip abroad as something akin to going into space. In 1970s, on his way home from Rome, the artist left the following lines in his diary: “I’m almost 50. And I have never had a studio. No, I have it just the same. Donbass, Cherepovets, Volga-Baltic Waterway, Kirishi, the front and all my life is my studio”.

In the case of Vladimir Vetrogonskiy, a creative trip, the Soviet practice, most likely originating from The Grand Embassy of Peter the Great, was fully consistent with its name. In preparation of the journey, the artist would bind his own hardcover book, using fine watercolour paper. He used these books to register his passing, but very precise thoughts on humanity, upbringing, and the purpose of art.

The way in which the thoughts of an artist and professional are expressed differs favourably from encoded metalanguage overused by contemporary authors. For someone, whose youth coincided with war, the reflections on peace, humanism, beauty and the comprehension of art could not be reduced to the ready-made rhetorical phrases. In his diaries of 1960s and 1990s, Vladimir Vetrogonskiy time and again spells out strong and simple truths that are so unwelcome today. In 1991, he writes: “At times we, in place of water pipes, attach ourselves to the sewerage of the world culture… We take from the world culture its waste: immorality, skepticism lack of faith, cult of pleasure, depravity and money. Simple, natural feelings undergo inflation. That’s when the time comes for art to reach out to the hearts of people and to assert the sublime, the good and love”.

This assertion, filled with abstract concepts and ideas, seems almost indecent in its sincerity, and in tune with the semi-official rhetoric. However, Vladimir Vetrogonskiy was very clear on the meaning of “the sublime” and the good. He takes the position, familiar to many of his contemporaries, of an artist and a citizen who bears both the burden of his own soul and responsibility for his disciples and the traditions of the School. This is the perspective that doesn’t allow for the “creative freedom” or the “art that doesn’t own anything to anyone”. The very next page of the diary unleashes harsh criticism of Viktor Tsoi, a new ruler of the minds and an artist-citizen who has become a cultural hero.

The rhetorical ardor of his diary entries, his scanty notes reflecting on the spiritual path of an artist stand in sharp contrast to the natural simplicity and ease of his drawings. A rigorous, at times even bitter thought coexists with a fleeting image of reality, and, thus, the captivating atmosphere of the drawing makes you accept any of his judgments as the truth.

It’s very rarely that you can find a phone number or a card on these pages. The texts almost never dwell on the particulars of everyday life. There is no place there for the descriptions of dinners, hunting for rare consumer goods, or the list of expenses, all that is so offending to the eye in the diaries of great masters. Perhaps, only a couple of isolated entries describe Vladimir Vetrogonskiy treating Venetian gondoliers to “Kazbek” cigarettes, discussing social issues with Renato Guttuso and fending off caustic questions from the Western press. For example, why does the Soviet Union fall behind in arts despite its achievements in science and technology? Careful attention should be given to the hurried, illegible notes and drawings that testify to the encounters with masterpieces. Vladimir Vetrogonskiy eagerly visited museums and cathedrals, where he, a practicing teacher and connoisseur of Western art, made sketches of “Girl with a Pearl Earring” by Johannes Vermeer, or of works by modernist artists, whose names he listed in his journal as if to attest the acquaintance.

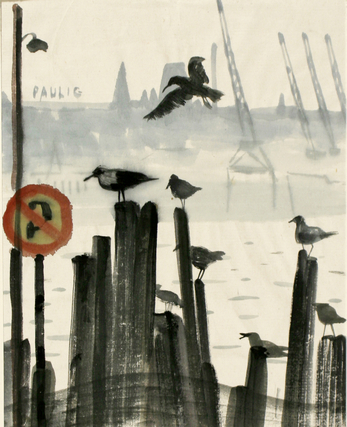

Drawings from the diaries as well as some of the artworks presented at the exhibition were made on the spot with several pencil lines. Later, in the hotel room, the artist would complete them with watercolours. Some of the works were done, however, exclusively with watercolours, which require a firm hand and a skill. Each of these pieces, created on the road, represents an intersection of spiritual, visual and professional experience.

Andrey Vetrogonskiy at home

Having received a longed-for studio, Vladimir Vetrogonskiy largely concentrated on sorting out and revision of the works he had done “on the road”. Compared to his father, Andrey Vetrogonskiy leads a more settled way of life, working in comfortable family studio on Literatotov Street that has become — along with Dom Matyushina — a local landmark of Petrogradskaya Storona.

As it happens, Andrey Vetrogonskiy has followed in his father’s footsteps. After graduating from famous Secondary Art School, he continued his education in the easel graphic art workshop of Academy of Arts under the guidance of Vladimir Vetrogonskiy. In his diaries, Vladimir Vetrogonskiy addresses the subject of the school and upbringing on numerous occasions. He refers to his son as “a poet” and underlines the development of the independent creative personality: “The son is mine, but the mind is his own”. Naturally, there has been the conflict between generations when Andrey Vetrogonskiy youthfully rejected his father’s poetics. The conflict was left behind long time ago. To date, Andrey Vetrogonskiy himself has a 20-year-old teaching experience, gained by observing the mistakes and delusions of developing artists.

Expressive urban landscape in Andrey Vetrogonskiy’s works points to the everlasting yearning for home. There is little of interest in quotidian and routine Odyssey of a common citizen, while the artist has his unforgettable encounters and experiences even behind the wheel of a car. It is about encountering the light. Andrey Vetrogonskiy’s paintings show the same streets, avenues and squares, the places familiar to many: Leo Tolstoy Square, Television Tower, particularly favoured by the artist, Medikov Prospect, or majestic bridges overloaded with the traffic flow. Easily recognizable Petersburg of these paintings seems to turn into a very generic city, filled with a somewhat angular modernist architecture. Natural light, November sky suddenly brightened by the sun, or evening purple glow from the light of street lamps and countless red flashes of headlights transform Andrey Vetrogonskiy’s Petersburg beyond recognition.

Once, in just a few drawings, Vladimir Vetrogonskiy caught the bustling atmosphere of the post-war cities, lit by electric lights from advertisements and the traffic. He was more interested in eternal, timeless views, such as that of the Seine, or St. Peter's Square. Nowadays, calm and quiet St. Petersburg has turned into vibrant European city. Andrey Vetrogonskiy’s paintings picture the cars and passers-by hurrying somewhere guided by the red traffic lights and barely noticing the drama of their own lives, which is played out in the magnificent scenery of the evening sky pierced with the radiant Television Tower. Andrey Vetrogonskiy’s urban landscape communicates the perception of a spectator who between all of the hustle and bustle has stopped to admire the play of light on the temporarily empty billboard between the shopping mall and dilapidated constructivist monument. The artist experiences the beauty in everyday life of a city dweller so intensely that he has to employ all the possible tools, ranging from the spray paint true to the spirit of the street art to painting brush, or oil pastels. Back at the studio, Andrey Vetrogonskiy evokes his colour impressions from the Television Tower experienced afresh or from the golden arcs of fast food restaurant, glowing with yellow light. This artistic approach has something in common with the asceticism, practiced by romantic landscape painters of the XIX century. Just like them, Andrey Vetrogonskiy does not re-create on his canvas a familiar landscape, but the spirit, confined within it.