Lyrical approach to reality can't be a goal or a method in Russian contemporary art. Those who disagree, doom themselves to a marginal existence outside the professional community and the whole industry of contemporary art

A. Erofeev, a protagonist of ideas of the 90s, distinguished three types of contemporary art: conceptualism, conformism and idiotism. Conceptual art explores itself, conformist art caters to political and market conditions, and the idiotic one vacuously decorates offices and bedrooms.

The presented art does not fit into the suggested typology since it uses painting for the intended purpose, regardless of the market or politics. This undescribed, large, self-contained and stable segment of fine arts exists somewhere in the "blind zone" of professional optics.

"Painting" in Russian language has two meanings. On the one hand, it is a technique, and on the other, it is some kind of esoteric power that enlivens a painted image. The ideas of transformation of painting into a spiritual practice, fetishization of image, and equating artists to demiurges used to flourish among those who were connected to the official and unofficial art of USSR in the 60's, but the younger generation of the 70's uncompromisingly criticized such position. In the 80's, the issue became a watershed between the cohort of reformers and the ones less enchanted by the innovations. The reformers considered painting an archaism, a part of the totalitarian heritage and an obstacle on the way to assimilation of new artistic strategies. The conservatives saw in painting a possibility of personal expression, cultural relic, and adequate embodiment of spiritual experience.

The energetic pressure of innovators and post-Soviet social reconstruction resulted in repressed aesthetic minorities. That was enough to enter interests of contemporary art.

Having left the reformers alone with their social battles, the "old believers" nevertheless preserved their art confession. In the late 90's and early 2000's, the gap between quiet, small, ever-understanding and friendly audience, and the noisy world of contemporary art seemed insurmountable.

However, recently we see examples of interpenetration and reduced tension between the former adversaries. Cultural activities in a prison mental hospital and a series of prisoners' portraits by M. Tregubenko, a portrait gallery of migrant workers and an exhibition in a chain food store by E. Golant, on the one hand are inscribed into the general trend of social disinhibition, and on the other hand are natural for authors' individualities.

It's impossible to distinguish such "thoroughbred" art with a cold look, aberrated with innovative itching. There is always a figure of a colleague–friend–guru, a personage from the epoch of informal culture of the 60s-80s, which inherited the art of the 20s and 30s by N. Lapshin, V. Greenberg, J. Vasnetsov, T. Mavrina, P. Basmanov, V. Ermalaeva, A. Labas, V. Sterligov and L. Yudin.

The second generation of Avant-garde, which dates back to this genealogy, while cushioning the superhuman nihilistic ambitions of their teachers, focused on the poetic and pantheistic experience of the world. On the background of repressions, labor camps, war, and famine, such an approach was a desperate theodicy and demonstration of the independence and worth of individuality. This view on the problems and the ethics of art reincarnated in the postwar informal culture and survived till today. For the first fifteen years of the contemporary Russian history it seemed an absolute relic. However, now, when the hopes for integration into the "big world" and normalization of all the aspects of the domestic life fell short, and when there is no more such a measured tread of contemporary art, the autonomous and all–sufficient artists' position obtained a new foundation.

In fact, it seems that for all twenty-three years of post-Soviet Russian history we have been steadily developing distrust of the world. The market-oriented economy has got off to a bad start; democracy has become a synonym of disorder and frustration, and the common welfare is not even worth speaking. The constitutional crisis of 1993, economic crisis of 1998, financial crisis of 2008, denominations, defaults, debunking, corruption, bent cops, abuses of elections... The instinctive wariness arises in relation to any external abstracted reality. A growing feeling of alienation and hostility of the external world makes people highly appreciate their private lives.

Uniting artists by gender may seem senseless if not the affinity of principles, approaches, and images. These features form a certain trend of artists of different education, age, and social activeness.

Female artists usually stay very alert to the changes in the world. Street kiosks and venders, coster mongers, open markets, shopping pavilions, and malls — each new "grin of capitalism" in the city becomes the object of creative attention. It is not a chase of seamy side, exotics, social criticism or market mechanisms research. It is an effort of experiencing, living, taming and getting along with the reality.

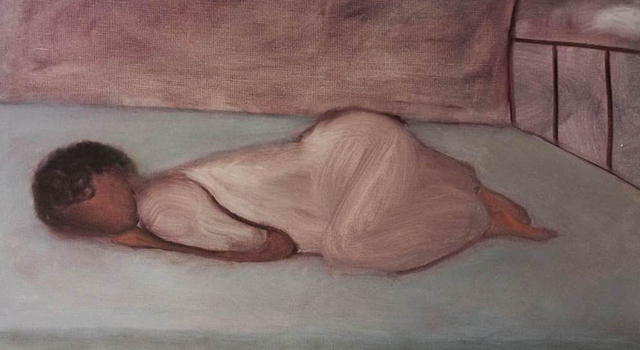

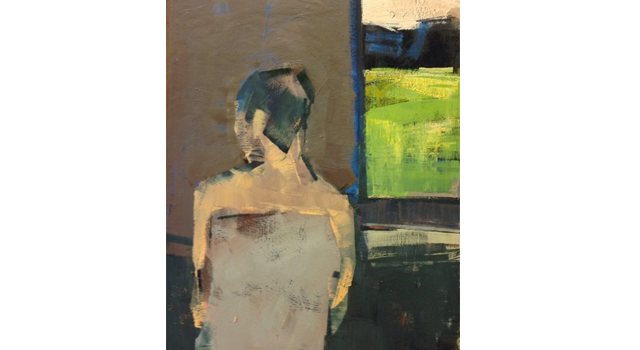

Great efforts are spent for defining and neutralization of the foreign, hostile, and suspicious. The authors, each in their own ways, try to protect comfort and integrity of the inner world from the outer freezing cold. For I. Vasilyeva and E. Golant it is enough to reflect the problem in painting. And it turns from something typical, cold, glossy and mass into something clumsy, handmade, lively, family–like and, in the case of Vasilyeva, folk. A. Belle reaches epic simplicity and emptiness. The oils on her canvases feel like the primary matter that is caught in the process of nucleation of the objective world. J. Zaretskaya recently has been looking at the world from her studio window and aching what she sees. J. Sopina, T. Gubaryova and M. Tregubenko drown everything they don't need or don't accept in a multilayered colorful wildness. T. Sergeeva carefully crops and comments on the depicted, not allowing any unnecessary information and random thoughts to get into the frame. S. Badelina, N. Everling and L. Golubeva fill their paintings with vibrant neo-realist emptiness.

The heroines of this exhibition intuitively choose subjects "within walking distance": a kitchen window view, road scenes, purchases in the nearest shop, dresses, kitchen utensils, church, children, courtyard, house, village or a tourist trip. The things that can be unquestionably trusted and associated with themselves.

Three "K", which Wilhelm II used to describe the social role of women, are provocatively inserted into the title. It is an intuitive artistic choice and a vote of nonconfidence to the "big world".

Curator: Alexandr Dashevsky.

The project was first implemented in "KultProekt" gallery in Moscow under the festival "Invisible Border".