From August 12 Erarta presented an exhibition “Things that never happened”

“Everything exists”: that is one extreme

“Everything doesn't exist”: that is a second extreme.

Everything is emptiness — that's the truth of the Middle Way.

Nagarjuna

“Things that never happened” is an interesting exhibition experience of young artists who met in F. Kovalenko Krasnodar Art School. Each participant has a serious artistic background. Alexey Spirenkov graduated from The V.I. Surikov Moscow State Art Institute and now has his own students. Alexander Kompaniets graduated from I. Repin St. Petersburg State Academic Institute of Fine Arts, Sculpture and Architecture. Viktor Ponomarenko has recently defended his graduation project. Ivan Streltsov turned to intensive studying of art history and prefers summers archeological expeditions to experiments in the studio. Of course, for each artist the years of apprenticeship and creative practices were of a different rhythm. Though, surprisingly, their works share similar elegiac atmosphere. The reason is probably media. “Things that never happened”, in many respects, is a portrait of the current situation in academic painting.

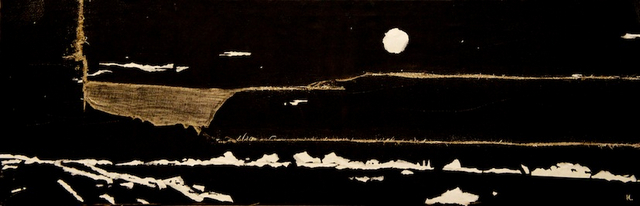

The artists with one assent approved the paradoxical and intriguingly mysterious exhibition title. In fact, any archaic myth about the world structure, and any historical legend can be called a thing that never happened. The artists also have their own questions to the world; this allows them to model their own myth using the tools they are perfectly skilled in. Their main subject is the life of matter that can be considered the modern mythology, since the truth still slips away both from the physicists and philosophers. There was a time when thunder was identified with The Chariot of Zeus, but the scientific description of the phenomenon is no less poetic and mysterious. Indeed, there is nothing happens in this paintings and sculptures. At the same time the White Sea landscapes by Alexey Spirenkov; masterful and finely skilled still lifes by Victor Ponomarenko; decorative textures by Alexander Kompaniets and nihilistic blank canvases by Ivan Streltsov are full of drama. And again we are talking about the death of painting and the victory of matter. About the triumph of life, to be more specific.

In the article “New Storytellers in Russian Art”, from the catalogue of an exhibition at the Russian Museum, Alexander Borovsky says that the artists of the twentieth century intentionally abandon narrative and subject images. The main reason was the common fatigue from the literature-centric nature of Russian culture, exerting in grand-sounding critics and didactic plots. The didactic function of Soviet art served the ideology, which unavoidably sparked disgust. Thus, glancing over a series of still lifes by Victor Ponomarenko, we can come to a false conclusion that we see formal sketches of a painter being entertained with his own craftsmanship and that these still lifes mean the author, in fact, has nothing to say.

There are a number of different and quite boring judgments that painting evolution ended in the XVII century, and that painting is no longer adequate media for our times. But by a mistake it stays alive, reproducing itself. In 2010, a Moscow artist Vladimir Potapov recorded a series of interesting video interviews on the topic of contemporary Russian art. The curator Viktor Misiano was just and convincing about this creation. Once again, having announced the death of painting, Misiano underlined its man-made and handicraft resource that was buried by the new media. Misiano says that the death of painting is just a metaphor. The era of painting dominance has gone, but the past is always a part of the present. Painting is dead, but it continues to exist, constantly looking back at the tradition. Memorial still lifes by Victor Ponomarenko is the bright confirmation. The object itself, the draperies, has a funeral aura, recalling tradition of covered mirrors and grave-clothes. Lamp is another frequent object of his works; it creates a dialogue between the tradition of allegorical still life and the motive of “memento mori” in the form of a burning candle.

But this burial aesthetics has another cheerful and carnival side, overcoming death. Let's go back to the title of the exhibition. “Things that never happened”: perhaps it speaks about artistic visualization of something unseen, which is akin to the radical practice of depicting of God, unacceptable to certain religions. In case of icons, this practice is regulated by stringent set of rules. We can assume that skills and artistry of academic school that all the exhibitors have passed through is similar to such a set of rules or an instrument to portray invisible and unknowable world of things, or in the absence of God — the matter. Alexey Spirenkov reveals specific relationships of the artist and the material. For example, the boards and sheets of rusted iron found on the shore of the White Sea, give impulse to a meditative session of plein air painting. Alexander Kompaniets is fascinated with beauty of wall cracks and wet asphalt texture. Victor Ponomarenko’s works resemble fairy tales by Hans Christian Andersen, based on the plots of secret lives of things, such as reflection of the collar or sadness of the abandoned Christmas tree. The very title of the painting “Still Life with a Hanging Drapery” refers to Anderson. There is a kind of existential pathos and tragedy of life, when the masterfully created still lifes become a reproach to the universe. It seems strange and frightening that these ridiculous gray rags exist at all, that they live their own lives, and that they will probably survive us. This uneasy feeling we find in a wonderful passage of Franz Kafka's “The Cares of a Family Man”, where he describes some living creature looking as a felt wad: Vainly I wonder what will happen to it. How could it die? Everything that dies, first has a purpose, pursues actions and therefore wears out and comes to the end; we can’t say it about Odradek. It means that under the feet of my children and my children's children it will still be rolling down the stairs, dragging the thread? Of course the thing undoubtedly harmless; but it’s almost painful to imagine that it will live much longer than us.

So in fact the announced absence of any narration is not quite true. The work of Alexander Kompaniets “Look” has a fair amount of that marginal “narration” in it; the implicit bloody story gets easily modeled by the viewer’s imagination. There is dramaturgy in upturned boats, wall cracks and cloths. We see the life of matter in literal and philosophical sense. In other words, we see the invisible movements of things in space and time. Certain conventional emptiness seems to be shown in the works of Ivan Streltsov, where the subject is the universe — the antithesis of matter. Once again we are facing the dead painting, looking back at itself. A nihilistic gesture of three identical canvases, filled with different black paints, Black Mars, Burnt Bone and Lamp Soot, could be interpreted as emptiness, nothingness and dialogue with Malevich. But! There is also admiration of the very physical substance and an attempt to understand it. According to the John Locke's sensualism theory everything we know, we learn from our own experience. Our knowledge is limited by the ideas of our own experience. And the idea of the matter is not quite clear.